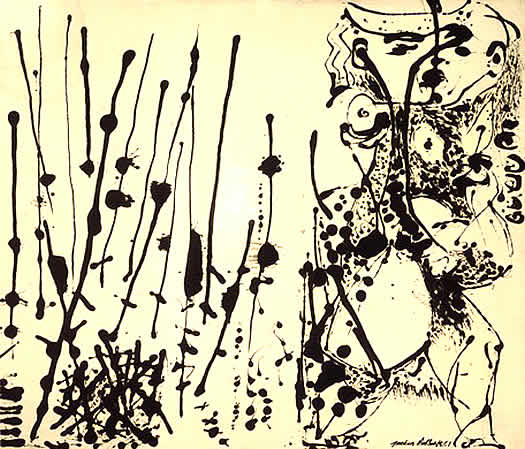

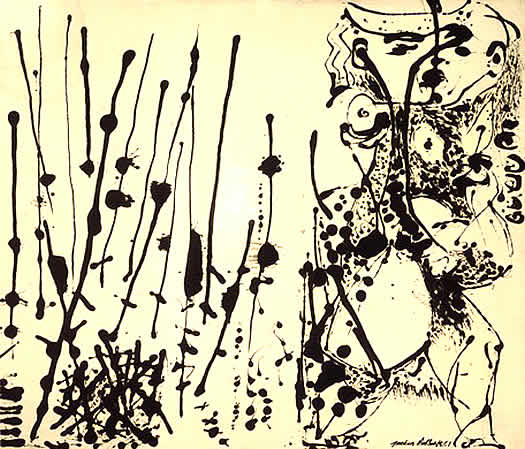

May not a Pollock forgery that passes for authentic be the best Pollock of all?

- asks Don Foster in a

recent article in N.Y.Times.

Here is a more of the article, which will soon be unavailable for free reading:

LAST year, 24 paintings were unveiled as previously unknown works by Jackson Pollock. (...)

But Richard Taylor, a physics professor retained by the Pollock-Krasner Foundation to subject six of the paintings to computer-assisted analysis, discovered that the paintings may well be fakes — at least, the drips lack Pollock's characteristic geometric pattern. The collection's owner disputes that this finding is conclusive.

At the heart of the controversy lie critical questions about artistic meaning and value that have vexed literary scholars no less than art historians. Would the exposure of a hitherto successful forgery diminish Jackson Pollock's reputation as a unique creative genius, by demonstrating that his work is replicable? If Shakespeare were credited with a mediocre poem hitherto presumed to be written by a lesser light, would that change our opinion of Shakespeare?

"What matter who's speaking?" asked Michel Foucault, quoting Samuel Beckett.

What matter whose painting? The implied answer — no matter at all — takes for granted that cultural artifacts are symptomatic of the society that produced them. The critic's job, then, is to assess the product on its own merits, quite apart from the artist's name or reputation. If "Hamlet" had been written by Christopher Marlowe or Edward de Vere, not by William Shakespeare, would the text therefore be less great? Perhaps not, but we would think of it in a different way.

If a previously authenticated Pollock painting was actually done by a disciple, or by Norman Rockwell, or by a monkey with a paintball gun, yet looks to be authentic Pollock, so what? The look-alike might be worth less at Sotheby's, but would it be worth less as art?

At stake in such attributional debates is a question of methodology: how can experts tell the difference between the real thing and an imitation? If the qualitative judgment of Pollock or Shakespeare scholars differs from quantitative analysis of a computer-assisted study, whose verdict will carry the day? That Richard Taylor's analysis can inform us of patterns generated by Pollock much of the time provides no guarantee that Pollock reproduced those patterns all of the time. But if the Pollock canon includes a forgery, it may be that Taylor's analysis provides a more objective mode of analysis than aesthetic appreciation.

(...)

In the art world, the problem of attribution is complicated by market value.(...) if you have paid, say, a half-million for a Pollock painting and some physicist and his computer say that you were hoodwinked, the question of the work's value is not wholly aesthetic.

Literary and art attribution is not just a game of pin the name on the donkey. A community of interested scholars must consider all available evidence, and come to a consensus. In the case of the Pollock canon, the jury is still out. It would be a mistake, in my opinion, to sell the disputed Pollock canvases at a discount without more evidence than computer-assisted analysis of drip patterns.

Meanwhile, Jackson Pollock may be chuckling in his grave: if the object of Abstract Expressionist work is to embody the rebellious, the anarchic, the highly idiosyncratic — if we embrace Pollock's work for its anti-figurative aesthetic — may faux-Pollock not be quintessential Pollock? May not a Pollock forgery that passes for authentic be the best Pollock of all?

Well, may it not? This question joins the recent

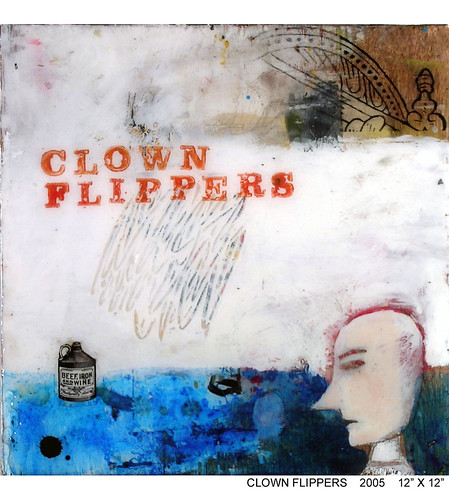

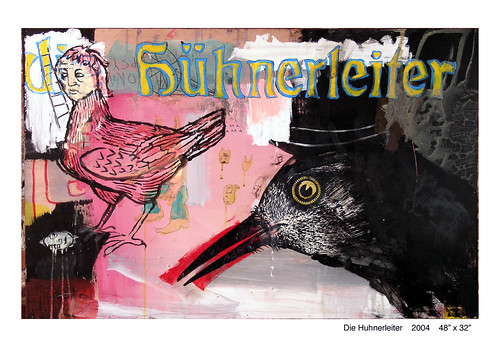

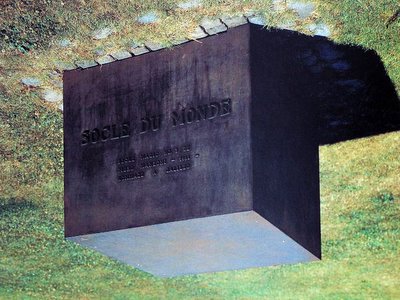

Duchamp controversy and many, many other cases where an artist's desire for artistic freedom seems to be forgotten when his works are judged by computer programs or valued for their size, or put on a pedestal and turned untouchable.

There is one factor, however, that tends to be forgotten in all our excitement about the

real meaning of art and its heroes. I mean psychology of art. Namely, two points about it:

1) As art viewers, we feel the need for coherence. The work has an artist, the artist has an identity, the identity is not just some drips of paint scattered across the canvas of the soul, but it is a whole, it makes sense. In this case, it means a) Pollock was a painter; b) Pollock was a good painter; c) Pollock's paintings are related to a) and b); finally, d) we can

expect that Pollock's work can only be his (there

are recognizeable patterns, then).

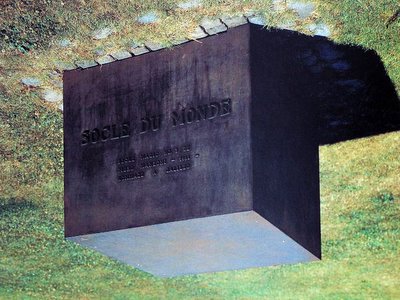

This final point is the most questionable, and obviously we often fail at it, misjudging a work, attributing it to the wrong painter, etc. But our failures are only more proof of the possibility of success. And if we wish to name some of the 20th-century works of art that are based on "anonimity", such as Yves Klein's exhibition of air, we must notice that they were conceptual works of art, and we are ready to pay either for the event (as a performance of burning money), or for the signs of the concept (as the partiture of Cage's

4'33). The silence, the air, we somehow don't actually assign to the artist. Earth, after all, is not Manzoni's.

2) Reality check: artists aren't always right. Not even about their own work. Pollock might have dreamed of " the rebellious, the anarchic, the highly idiosyncratic", but he never moved beyond the canvas (he never even made the tiniest hole in it, as Fontana ever-so-modestly mentioned). Artists say a lot of things. And dream of even more. That's our job. If we don't dream, something is wrong. As Jules Verne put it,

there are no great achievements without exaggerated expectations. But if this is true, we simply cannot take the artist's word for it. Or at least, we don't need to. Not even when they're dead and famous (

what a scary combination!). That's why we might just pay more attention to our way of seeing

The Fountain, or a drip painting, than to that of the artist. After all, if we listened to the wonderful, charming

futurists, we wouldn't even know them.

I suppose if we join the dots 1) and 2), we see that the artists need a story and we need one. Trying to make us forget any story and see the "pure drip value" of a Pollock seems absurd. On the other hand, promoting the avant-garde tendency towards anarchy as a way of promoting the very artists that lived this tendency is, well, silly. Damn it. We actually need the library, and we need the museum. And some of us, yes, would like to know if the drip-dropped canvas they own was made by a genius or not. Does it change the value of the canvas? Of course. Why? Because we need the story.